The Bluthner Piano And The Hindenburg Airship

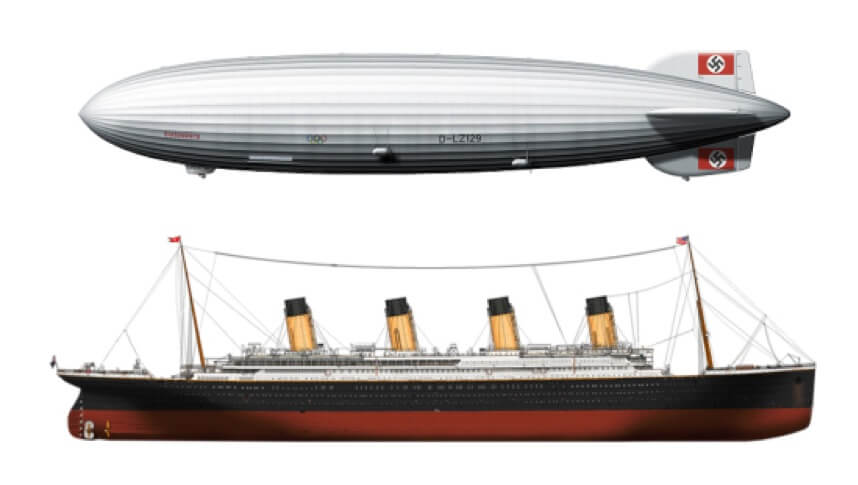

It is difficult to imagine an 804-foot-long airship floating in the sky. That is the length of two and a half football fields, end to end. Such was the size of the famous Hindenburg. It was powered by four 1,100-horsepower diesel engines, giving it a maximum speed of 84 mph. It was often compared to the Titanic in size.

The first of these flying whales was designed by Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin, a retired German army officer in 1900. It was half the size (420 ft.) of the Hindenburg and flew at 20 mph. The cigar-shaped dirigibles had covered frames that housed a number of gas filled cells, but remained rigid whether filled or not.

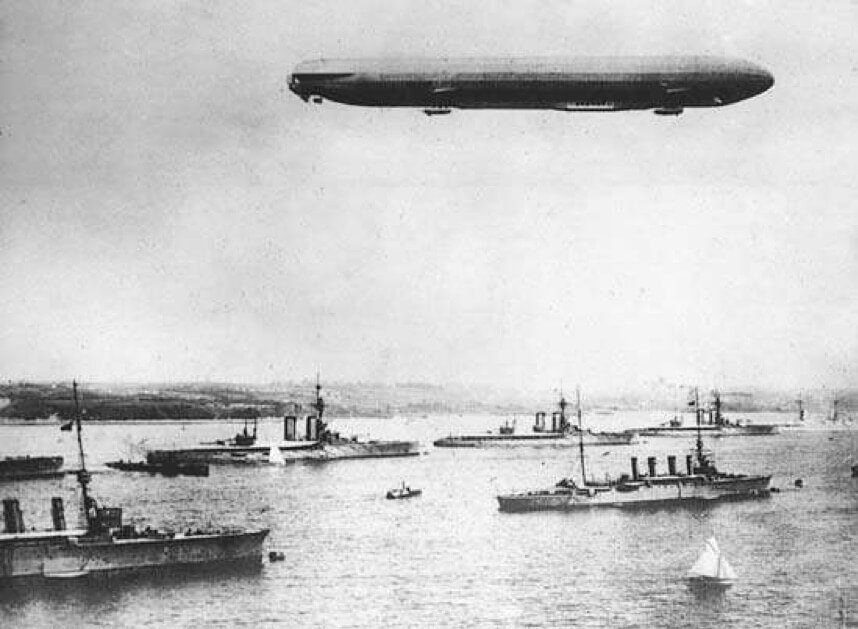

In World War I, Germans used the zeppelin-type airships for long-range bombing missions because they could go higher than airplanes in those days. Twice in 1917, zeppelins flew for nearly 100 hours, leading people to believe they would figure prominently in the future of aviation. Germany gave a number of these airships to the Allied Powers countries as part of postwar reparations. (Reparations of $33 billion were later reduced, but in the 1920’s resentment over reparations was used by German ultranationalists to foment political unrest.)

Between the wars, the two most famous zeppelins were the Graf Zeppelin, (776 feet long) completed in September 1928, and by 1937 had made 590 flights including 144 ocean crossings and flown more than a million miles; and the giant Hindenburg, first flown in 1936.

The Hindenburg used cutting-edge airship technology, and was one of the most capable aircraft of any kind in its time. Hindenburg had advanced innovative engines, an auto-pilot, and a sonar altimeter among other things, and it could carry a greater payload a farther distance than any other aircraft of its day.

The First Piano in the Sky

The Hindenburg featured the first piano ever carried on a passenger aircraft.

Dirigibles had strict weight limits, so when the Zeppelin company commissioned a piano from the renowned German piano builder, Julius Blüthner Pianofortefabrik, it need to be lightweight. Typical small grand pianos weigh about 500 lbs., so Blüthner used an aluminum alloy to create a small grand piano that weighed 356 lbs. The frame, rim, fallboard, and top lid were made of duralumin, and the legs, back bracing, and lyre were made of hollow duralumin tubing. A reporter for the Associated Press who was a passenger on Hindenburg’s maiden voyage to the United States, is quoted as saying that the piano had a “particularly large and full tone” despite its aluminum construction.

Architect Fritz August Breuhaus was the interior designer and decorator for the airship. He also designed the case for the Bluthner piano. It was covered in pale, lightweight pigskin that had a warmth that complimented the instrument’s excellent tone.

The piano was placed in the lounge of the Hindenburg on A Deck. It was often played by passengers and the ship’s musical captain, Ernst Lehmann. On the older aircraft, the Graf Zeppelin, Lehmann had entertained passengers on accordion.

The Blüthner piano was a highlight of the Hindenburg’s first flight to America in 1937. Professor Franz Wagner, a pianist from Dresden, performed classical concerts as well as pop music for the passengers. As the dirigible approached the coast of North America, he played Schubert’s Serenade and Strauss’s Blue Danube, broadcast live on NBC. He also accompanied passenger, Lady Suzanne Wilkins, the wife of Australian explorer, Sir Hubert Wilkins, singing, “I’m in the Mood for Love.”

When the couple was interviewed later, they claimed the accommodations were even better than the old Graf Zeppelin. Lady Wilkins spoke of a storm that had no effect on the ship or passengers and nobody had suffered motion sickness.

Bluthner was proudly represented on the first flight by Dr. Rudolf Bluthner-Haessler.

The Last Dirigible in the Sky

Though it was designed to be filled with helium, the Hindenburg was filled with highly flammable hydrogen. Export restrictions on helium (among other things) by the United States against Nazi Germany created the need to renovate the dirigible for easily-obtained hydrogen. In 1936 the Hindenburg inaugurated commercial air service across the North Atlantic by booking 1,000 passengers on 10 scheduled round trips between Germany and the United States.

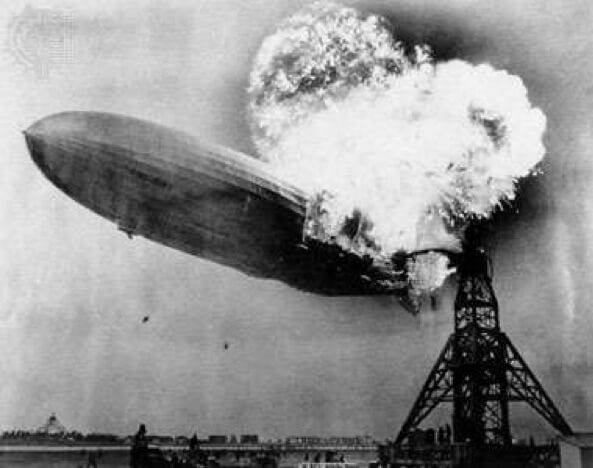

On May 6, 1937, on only the second of its scheduled 1937 transatlantic crossings, the Hindenburg burst into flames while landing at Lakehurst, New Jersey.

Out of ninety-seven people aboard, 35 were killed. Men, women and children. One member of the ground crew also perished. The fire was officially attributed to a discharge of atmospheric electricity in the vicinity of a hydrogen gas leak on the ship’s surface. There was speculation that the dirigible had been the victim of an anti-Nazi act of sabotage.

There were also two dogs kenneled on board, both died in the fire. One of the dogs named Ulla, a German shepherd, belonged to a passenger who survived. Joseph Spah was a German acrobat who used Ulla in his acts. An immigrant, now living in the United States, they were returning home after a European tour.

The dogs were held in a restricted freight space, and their owners had to be accompanied by a crew member to feed and visit their pets. Spah sometimes went alone and was caught doing so. Because of these unauthorized visits, he was considered to be a possible saboteur, using his dog as a cover for planting a bomb. He was able to jump from the Hindenburg while it was roughly 20 feet from the ground. He broke his ankle.

He was investigated by the FBI and cleared, although many continued to believe he was guilty. Others speculated that the disaster might have been pilot error by turning too sharply and breaking a tension strap that ripped a hole in a gas bag, and causing static electricity to ignite it.

The Hindenburg disaster, which was recorded on film and on phonograph disc, marked the end of the use of rigid airships in commercial air transportation.

The Hindenburg piano was spared as it had been removed from the airship before the beginning of the 1937 season and taken to the Blüthner factory, where it was placed on display. However, the piano was destroyed in 1943 when the factory burned following an air raid during the Second Word War.

After the war the East German government permitted the Blüthner family to rebuild because the Blüthner piano was considered a national treasure (and also because the Soviet Union needed quality pianos). With the liberation of Eastern Europe, Blüthner is again privately owned by the Blüthner family.

Blüthner is the only piano maker who builds a complete line of high-end acrylic pianos in models ranging from traditional to futuristic. (Other manufacturers may have a single model in their line). Euro Pianos Naples proudly represents this full line of beautiful Lucid Bluthner crystal grand pianos which are featured on our website.